LPs have long viewed emerging managers as a high-risk, high-reward proposition: a potential source of outsized alpha in buyout portfolios, but with elevated downside and capital impairment risk. This perception has often pushed emerging managers to the margins of portfolio construction.

In this paper, we test whether that reputation is warranted. Using data, we assess whether emerging managers truly represent a disproportionate source of risk—or if the opportunity has been mischaracterized.

While the high-risk, high-reward label contains some truth, our analysis suggests that the risk profile of Fund I vehicles in particular has been overstated. In practice, the data suggests outcomes are skewed toward the high-reward end of the spectrum.

LPs that avoid Fund Is are leaving a powerful source of alpha on the table. Capturing that alpha, however, is not automatic. Successful emerging manager programs require disciplined manager selection and an understanding of the unique (but manageable) challenges associated with early-stage funds.

Methodology

This analysis draws on SPI, our proprietary data and analytics platform. This multi-decade array of vintages, strategies and market cycles provides a robust foundation for evaluating emerging managers’ performance.

For the purposes of this paper, we define an emerging manager as a GP raising their first, second or third institutional fund within a flagship buyout fund series. Our analysis focuses specifically on managers for which we have Fund I data, enabling a consistent assessment of early fund performance and subsequent the outcomes.

Emerging managers represent about 40–45% of our primary deal flow annually, underscoring their importance to the private equity ecosystem and the necessity for rigorous and customized evaluation frameworks. We accordingly conduct extensive diligence on a large and representative sample of these managers each year.

The brass tacks: early funds outperform

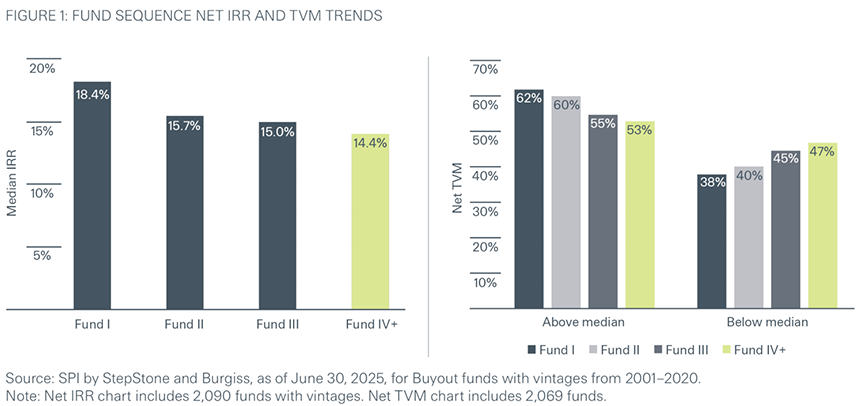

Across multiple performance measures, our data suggests that early funds outperform, with performance declining progressively as fund sequence advances (Figure 1).

On an absolute return basis, Fund Is significantly outperform later funds. While performance tends to degrade over time, Funds II and III continue to deliver strong absolute returns. These trends hold true with respect to relative performance. The likelihood of outperforming the median is highest for Fund Is and gradually declines thereafter. Funds I and II exceed the median ~60% of the time, compared with ~50% for Funds IV and beyond.

We attribute this early-fund outperformance in part to stronger alignment between LPs and GPs. In many cases, managers have not yet accumulated significant personal wealth and remain highly economically and professionally invested in the success of their early funds. Early funds also tend to benefit from direct founder involvement in deal execution and from alignment driven by carried interest, as Fund I managers rarely generate substantial income from management fees given smaller fund sizes and higher startup costs.

Hunting for the ideal Fund I archetype

Our analysis suggests that early funds can generate relative outperformance, but it raises a natural question: is there an identifiable Fund I profile—or even an optimal founder profile—associated with stronger results? We analyzed our data across multiple dimensions to answer these questions, examining both fund- and founder-level data cohorts. While there is no magic recipe for a “perfect” Fund I, several patterns emerge among higher-performing emerging managers.

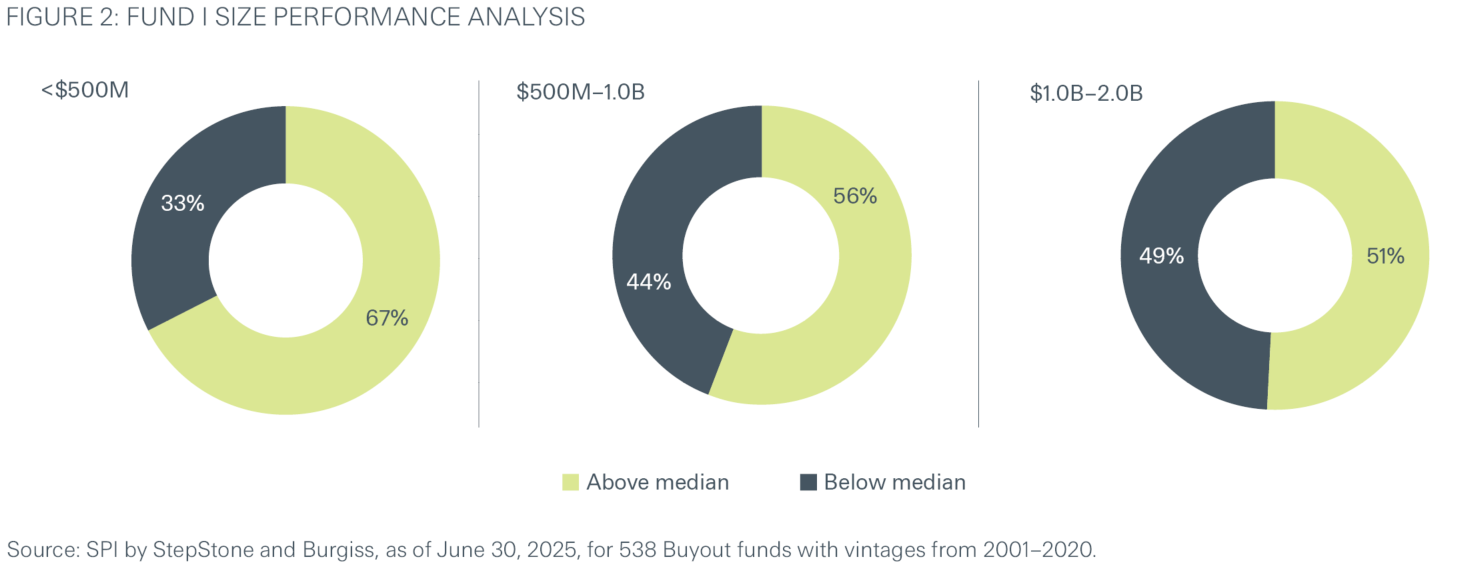

Smaller Fund Is do better

GPs that raise smaller Fund Is tend to outperform those that raise larger inaugural pools of capital (Figure 2). Fund Is with less than $500 million in commitments show a clear advantage, with 67% delivering above-median returns, compared with 44% for funds between $500 million and $1 billion. For funds above $1 billion, fund size shows no strong correlation with relative performance. While fund size alone does not determine outcomes, smaller inaugural funds are generally associated with investments in smaller portfolio companies, which often offer greater alpha potential through valuation inefficiencies, outsized value creation opportunities, and lower leverage. Smaller fund sizes may also support greater selectivity and discipline, contributing to stronger performance.

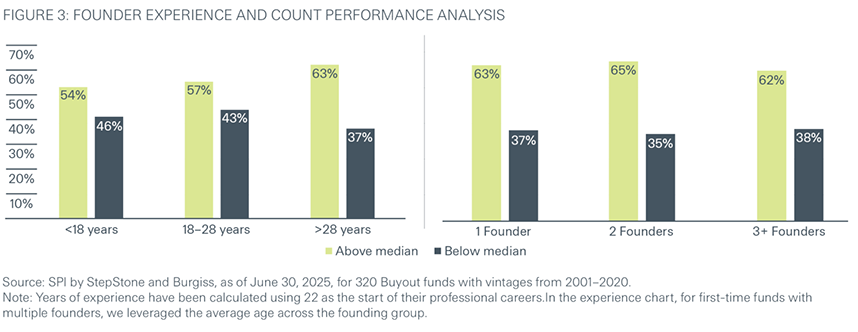

Experience matters (more than expected)

Founder experience shows a strong positive relationship with performance (Figure 3). This finding challenges a common belief that younger first-time founders outperform thanks to their greater alignment. Instead, the data suggests that years of experience matter more, with more seasoned founders benefiting from cross-cycle investment experience, more established and deeper networks, and stronger pattern recognition.

The number of founders doesn’t matter

While founder experience correlates strongly with relative performance, the number of founders does not. Performance outcomes are broadly similar for single-founder teams and those with two or more founders. Although key-person risk is inherent in first-time funds, expanding the founding group does not, on its own, translate into improved performance. That said, from a portfolio risk-management perspective, having two or more founders may still be preferable even if doesn’t show up in the numbers.

What’s the catch?

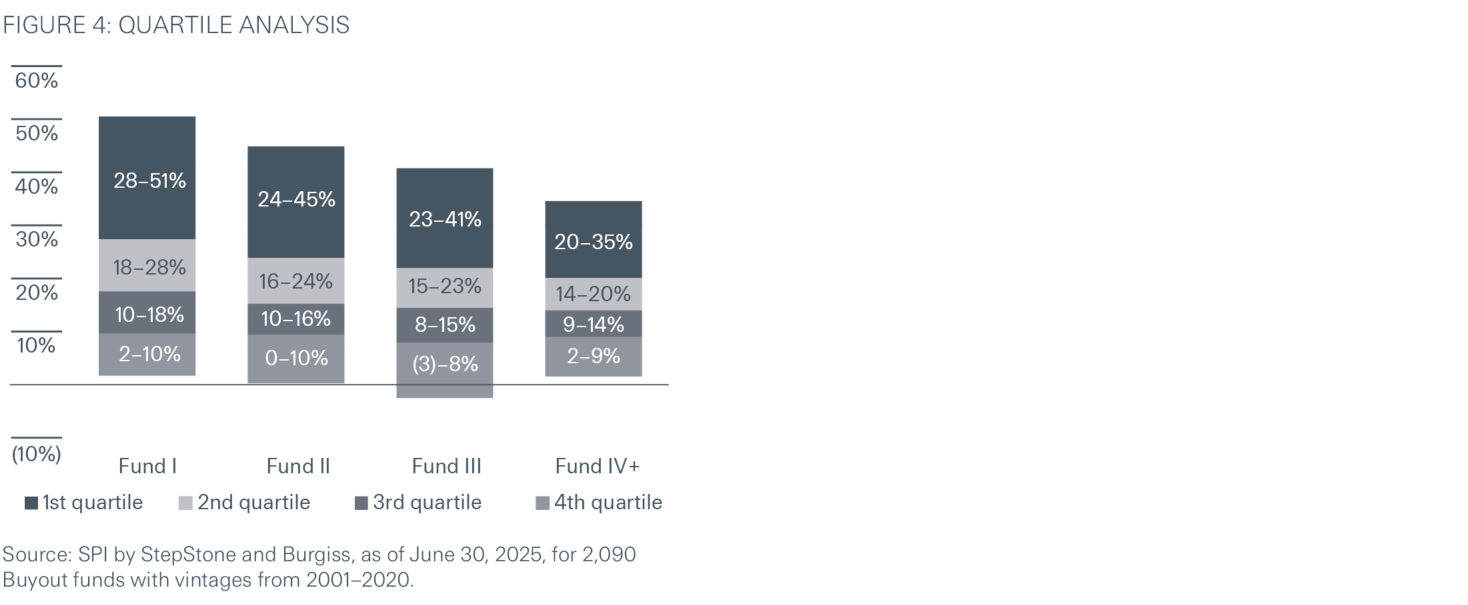

While early funds, in aggregate, tend to outperform later funds, not all Fund Is are created equal. Although the absolute risk profile of Fund Is appears lower than one might think, return dispersion is meaningfully wider (Figure 4).

Most of Fund I outperformance is driven by strong first- and second- quartile returns. Identifying the GPs with a higher likelihood of achieving above-median or top-quartile performance is critical to capturing the alpha potential that a successful emerging manager program can add to a private equity portfolio.

Playbook for emerging manager selection

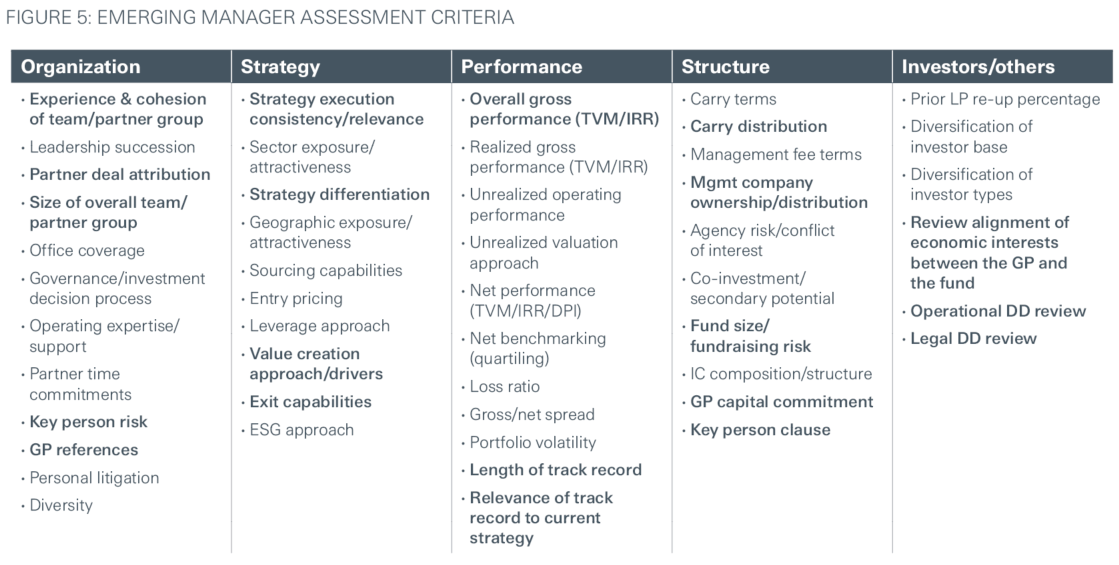

While many elements of fund diligence are consistent across manager types, emerging managers present a distinct underwriting profile that warrants deeper scrutiny in specific areas (Figure 5).

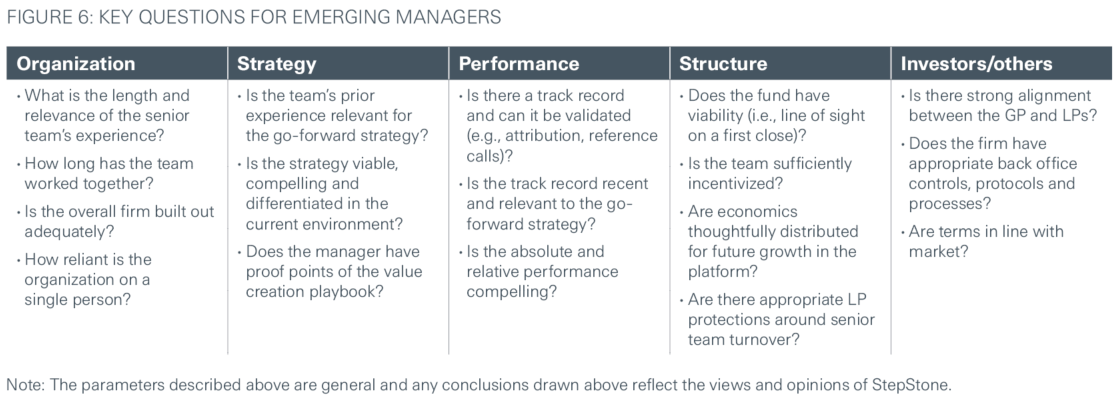

LPs should consider several questions when assessing an emerging manager. The answers to these questions can help to paint a clearer and more complete picture of institutional quality, relative attractiveness of strategy, attributable track record and team capabilities/stability (Figure 6).

Hang on, and don’t let go

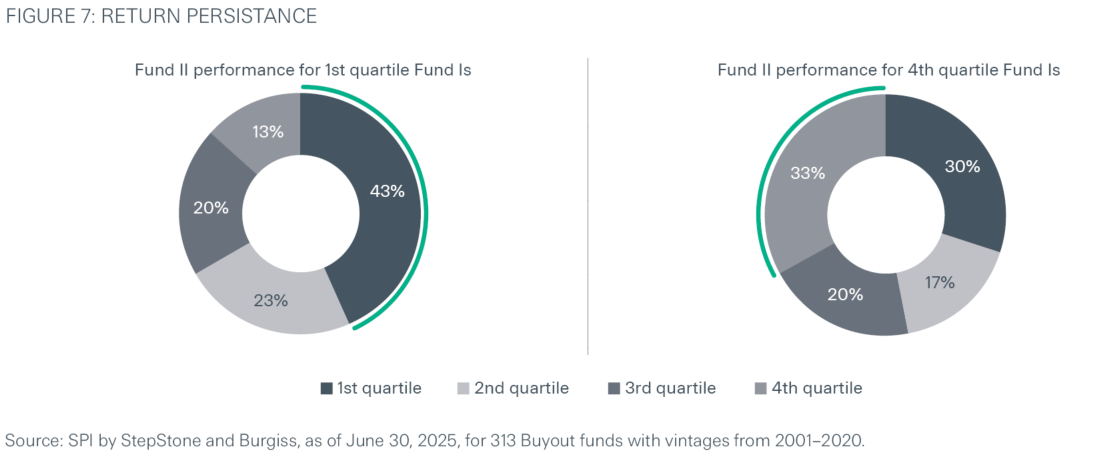

Successfully identifying a top-quartile Fund I can lead

to durable long-term partnerships and sustained alpha generation. Among managers that delivered first-quartile performance in their inaugural funds, 43% went on to achieve first-quartile returns in Fund II, while 66% delivered above-median performance (Figure 7).

But return persistence is a two-way street. One-third of managers with fourth-quartile Fund I performance remained in the fourth quartile in Fund II, and 52% continued to perform below the median.

Conclusion

For LPs willing to apply a disciplined framework, emerging managers—particularly Fund Is—can serve as an attractive source of excess returns within a diversified private equity portfolio. Maximizing the performance of an emerging manager program, however, requires skillful selection to navigate the unique risks associated with first-time funds. With the right framework, the odds of identifying a top-performing Fund I increases, which can lead to persistent outperformance and compounding value across vintages, and the formation of durable long-term partnerships.